King Blazed Trail for Others to Follow at UVA

By Jeff White (jwhite@virginia.edu)

VirginiaSports.com

CHARLOTTESVILLE – John Paul Jones Area is about to be the center of the Atlantic Coast Conference wrestling world. The ACC tournament will be held Sunday at JPJ, starting with first-round matches at 11 a.m. and closing with the 7 p.m. finals.

George King III, who enrolled at the University of Virginia in the summer of 1964, never won an ACC wrestling title. He was new to the sport, and his wrestling career at UVA lasted less than two seasons. But he’s still a pivotal figure in the history of the University and its athletic department.

King is believed to have been the first African-American student-athlete to compete for UVA. During the 1964-65 school year, he was on the freshman wrestling team that winter and joined the freshman lacrosse team in the spring.

Several more years would pass before Virginia began recruiting African-Americans for its teams. The 5-foot-6 King, a Charlottesville native who’d been a starter on the Lane High School football squad that went undefeated and won a state championship in 1963, walked on in wrestling and lacrosse at UVA, sports that were foreign to him.

“I hadn’t played them,” King, 75, said this week at the Dairy Market, a short walk from his home on 10½ Street. “Didn’t know the rules. Didn’t know anything about either one.”

But he followed a strict regimen of pushups, pullups and situps, “and I liked competing with other people,” King said, and so he accepted the challenge.

“I knocked on the door,” King said, “and the door opened without me using a battering ram or explosives. I didn’t have to say anything but ‘I’m interested in playing,’ and off we went.”

One day at Memorial Gym, King stopped to watch wrestling practice, and what he saw intrigued him. He’d played King of the Hill with his buddies in the neighborhood, as well as football at Lane, and figured he might be well-suited for wrestling. King asked one of the coaches if he could give it a try.

“He said, ‘Go downstairs and get some equipment,’ ” King recalled. “That was it. Same thing with lacrosse. I went down and got the equipment, came upstairs and started right away.”

He was the only African-American in either program, but nothing was made of that fact, at least not in front of him, King said. “No big deal. No fanfare. No nothing. Just another student coming in wrestling. Same thing with lacrosse. Once I was in, I was in.”

In the spring, King said, “the wrestling guys played lacrosse to stay in shape, so naturally I followed them. I didn’t know anything about the game, but I was a hustler and I was fit.”

King was a midfielder who took faceoffs. “I didn’t mind getting hit,” he said. “I didn’t mind thumping.”

He weighed about 160 pounds then, said King, who played offensive guard and linebacker at Lane. He’s now a trim 147-pounder.

At Lane, where his football coaches were Tommy Theodose, Joe Bingler and Ralph Harrison, King was one of four Black players on what’s believed to the first integrated team in Virginia High School League history.

Like those he played for at Lane, his coaches at UVA, including Butch Schwab (wrestling) and John Walters (lacrosse), “just treated me like a normal guy,” King said. “That’s the joy of sports. I found good people like that that were willing to take you at face value and let you show what you could or could not do.”

There was nothing written about King’s pioneering status while he was a UVA student, and decades passed before it was publicly acknowledged. In September, King and former women’s basketball player Sharlene Brightly were honored as UVA’s recipients of the ACC’s inaugural UNITE Awards, which were created to recognize people affiliated with the conference for their contributions in the areas of racial and social justice.

“Here, 50 years later, I thought it was a nice gesture,” King said. “It was a hole that needed to be closed. To go through the effort to verify it, I thought it was worthwhile to do, not just for the University but for the surrounding African-American community.”

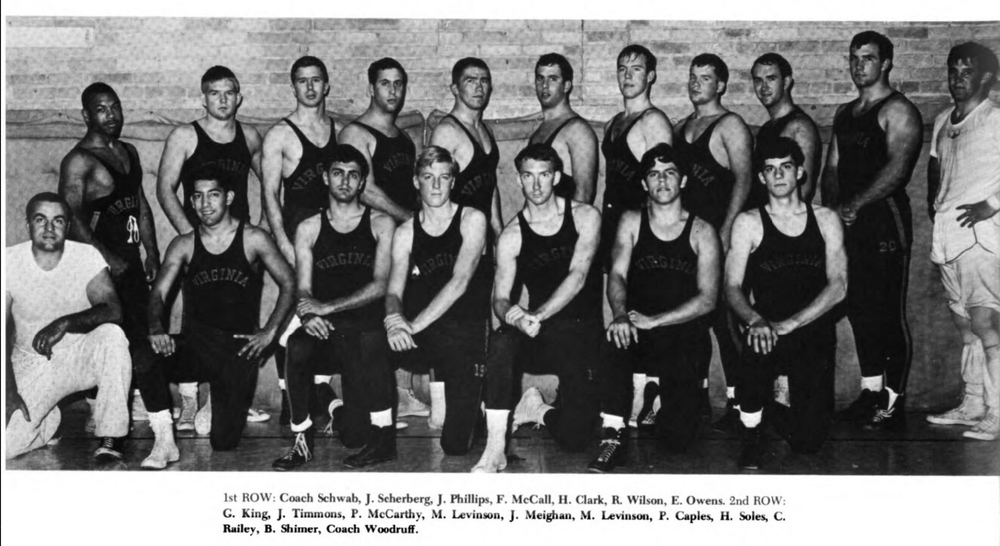

UVA's 1965-66 wrestling team

King, whose family lived on 13th Street, attended All-Black schools (Jefferson and Burley) until the 11th grade, when he enrolled at Lane High. He was one of about 40 African-Americans in the student body at Lane, where he excelled athletically and academically.

Bridgewater offered King a football scholarship, he said, and he could have attended Howard or Tuskegee on an academic scholarship. He decided instead to apply to UVA, which at the time had only a few dozen Black students.

His parents worked at the UVA Medical Center, as had his grandfather, who was the head baker, and King had started working for Dr. Albert Paquin in the Department of Urology as a high school student.

King said he applied to the University in part because “I wanted the status that went along with getting in. UVA was the holy grail of colleges to go to.”

After being accepted, he enrolled in the School of Engineering, with its demanding curriculum. “I bit off a little more than I could chew,” King said, laughing.

The University allowed him to live at home, and so his college experience differed from that of the average first-year student. “Ate at home, slept at home,” King said. “I went to class, practice, home. Class, practice, home. I wasn’t integrated into anything, really, but practice and the classes I was in.”

The University’s student body and faculty were virtually all-white then, and it “was a real cold environment [for Blacks],” King said. “But that wasn’t different from Charlottesville. Charlottesville was cold. This was the environment that was suppressing my uncles and aunts and cousins and friends in town, because they were the ones working as orderlies, janitors, food delivers and housekeepers [at UVA]. That was it. That was all you could aspire to.

“But the thing is, looking at it now, I don’t like feeling upset about things, because there’s more to my life than racial segregation and racism. There’s more to it than that. You had to be determined enough to push through it and smart enough to push through it.”

He and his fellow Black students “were bright enough to get in school, but all of us had different kinds of challenges with adjusting,” King said. He helped them find social activities in Charlottesville’s African-American community.

King began the 1965-66 academic year at UVA and made the varsity wrestling team. He finished the fall semester with a C-minus average, however, and was placed on academic suspension for the spring semester.

He planned to return to UVA for summer school, but King was drafted in the spring of 1966. He joined the U.S. Air Force that May. For most of the next four years, he was stationed in Charleston, S.C., which he found to be “much more Southern than Virginia,” said King, who learned a lot about civil rights during that period.

A flight line mechanic in the Air Force, King took extension courses to improve his GPA, but “UVA did not accept those credits,” he said. “I wanted to get back into school right away [after leaving the service], and Hampton accepted me.”

In 1971, King enrolled at what is now Hampton University, where he majored in math. He graduated in 1973, after which he took a job as a programmer analyst with Xerox in Rochester, N.Y.

“Then I fell in love, quit my job, and drove across the country,” said King, who moved to Southern California.

He later relocated to Australia and then to Atlanta before returning to Charlottesville in 1990.

King, who married in 1976, is now divorced, with two children: a daughter in Florida and a son (George King IV) in California. He has a niece, Precious King, who graduated from UVA in 1999.

A former president of the Charlottesville branch of the NAACP, King ended up working at the UVA hospital, like so many of his relatives, but in a different role. He began as a contractor doing computer programming for the housekeeping department and helped install an automated system that notified hospital personnel when a room was available.

“I came in at a time when the hospital was upgrading its ability to process information,” King said.

He later became the medical center’s director of dispatch systems and technology for inpatient transportation. Before he retired in 2010, King was working in IT security at the medical center.

In 1994 and 1996, research papers written by students in then-UVA professor Julian Bond’s history classes highlighted King’s experience as a student on Grounds. King has copies of those papers, as well as the certificates he received for his participation in wrestling and lacrosse.

Among those who signed the certificates were Steve Sebo, Virginia’s athletic director, and Thomas Krebs, chairman of UVA’s Student Athletic Council.

“These guys deserve a lot of credit,” King said. “They opened up sports at the University in 1964. I was given that opportunity among my peers, and I was motivated to go ahead and try, in spite of what might have appeared to be obstacles in my way.”

To receive Jeff White’s articles by email, click here and subscribe.

King (left) with son George King IV and grandson George King V