Black History Month Spotlight: Tommy Smith

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the second of the four articles in VirginiaSports.com’s Black History Month series for 2022. The others are on Cathy Grimes-Miller, Paulette Jones Morant and Keith Witherspoon.

By Jeff White (jwhite@virginia.edu)

VirginiaSports.com

CHARLOTTESVILLE – Dom Starsia came to the University of Virginia in the summer of 1992 to lead a men’s lacrosse program that had acquired an unflattering reputation. Tommy Smith was then a high school All-American in Manlius, N.Y., a suburb of Syracuse, and he was familiar with the knock on UVA in lacrosse circles.

“To be honest, what I always heard was that Virginia was soft,” Smith recalled Saturday. “All the talent in the world, but soft. They were not hardened.”

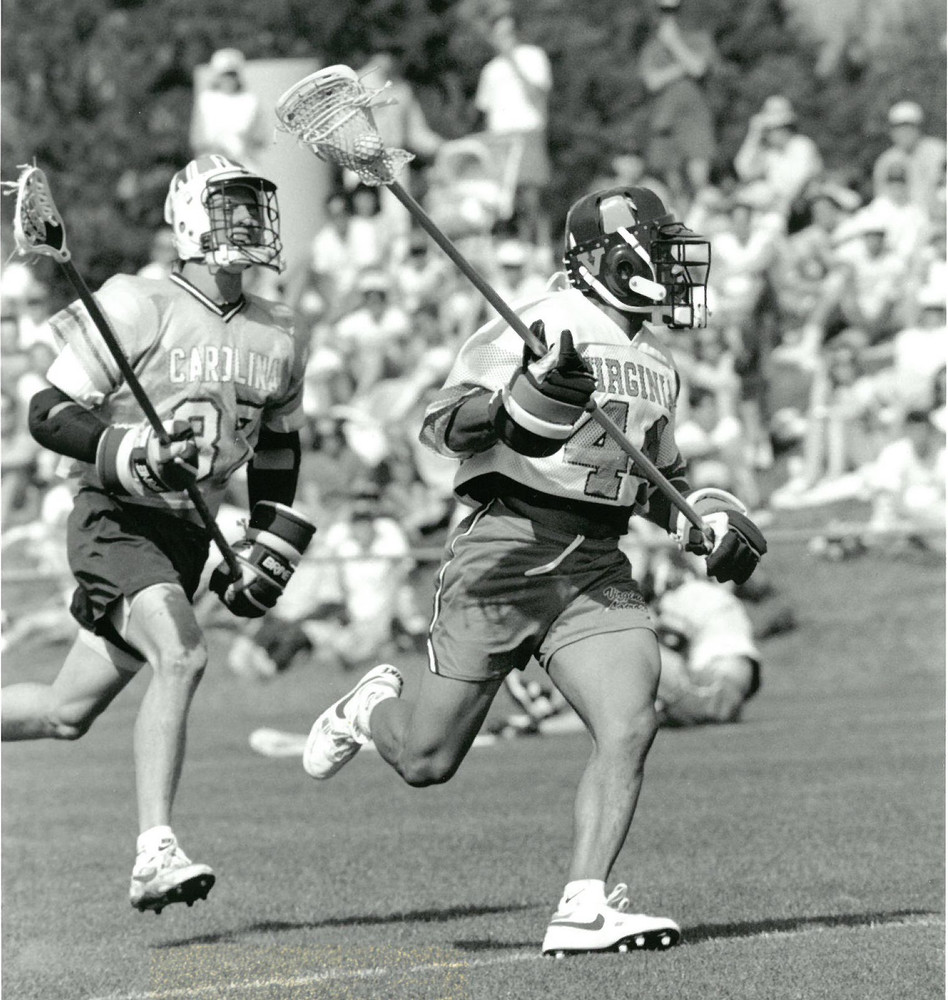

Smith helped change that perception, along with his fellow members of Starsia’s first recruiting class at UVA, including Michael Watson and Doug Knight. They arrived on Grounds in the summer of 1993. A 5-foot-11 defenseman, Smith became a three-time All-American for the Wahoos, who twice advanced to the NCAA championship game during his career.

To pull Smith away from Syracuse, then coached by the legendary Roy Simmons Jr., was a coup for the Wahoos, Starsia said. “He was a high-visibility public school kid from Upstate New York, and it signaled a little changing of the guard at Virginia.”

Smith said: “We brought that toughness to the program. We laid the foundation for what you see now. Unfortunately, we happened to lose [to Princeton in the 1994 and 1996 NCAA title games] my first year and my third year in overtime, which I still have nightmares about. But at the same point in time, to even get to that level, it was great.”

Smith’s father, John Smith Jr., was a renowned college football official with a no-nonsense personality. Tommy Smith brought some of that mentality to Starsia’s program, as well as a ruggedness common to residents of that part of the Empire State.

“The winters harden you as a person, physically, emotionally,” said Smith, who now lives in Norwalk, Conn. “They really do.”

The student body at his high school, Fayetteville-Manlius, was predominantly white, and that was the case at UVA, too. But that didn’t bother Smith, whose parents are graduates of Virginia State University.

“I was here to get an education and to play lacrosse,” said Smith, who graduated from UVA in 1997.

Syracuse, whose teams were then known as the Orangemen, had won three straight NCAA men’s lacrosse titles, in 1988, ’89 and ’90, and Smith knew all about that program’s storied tradition. Still, he wanted to experience life outside the Syracuse area, and he liked what he heard from UVA’s new coaches, Starsia and assistant Marc Van Ardale.

Moreover, Smith said, his parents grew up in Virginia. “My mom’s from Petersburg”––where she attended high school with Moses Malone––“and my dad’s from Suffolk. Not many people knew that. So we had family, maybe not around Charlottesville, but we had family from Virginia.”

His decision probably displeased a lot of people around Syracuse, Smith said, but he didn’t care, “because it’s my life. It was just one of those things where I wanted to leave.”

Also, he said, his parents “just loved Dom and Coach Van Arsdale. It made it pretty easy.”

Syracuse had long had African-Americans in its men’s lacrosse program, including Jim Brown, and that impressed Smith. “But I knew Dom was open and honest. He was like, ‘Listen, guys, I don’t care what color you are. I care about your character.’ ”

Smith joined a UVA program whose upperclassmen included two Black players: short-stick defensive midfielders Woody Moore and Mark Dixon. In 1994, when Smith was a freshman, he started at long-stick midfielder and played on the same midfield line with Moore and Dixon. They were called the Soul Patrol, a nickname that was not their creation.

“It was actually one of the white guys,” said Smith, who moved to close defense as a sophomore. “Some might say it could come across as racist. We did not think that at all. I kind of got a kick out of it, because we were the only three Black guys on the team, and we all played defense.”

If they were playing today, in the NIL era, the three of them might well be able to profit from the sale of Soul Patrol merchandise and endorsements.

“I know,” Smith said, laughing. “Believe me. The money we could have made.”

Moore and Dixon were outstanding students and, like Smith, were well-respected by their teammates. “Those guys were role models for the people we had in the program,” Starsia said.

There were often few, if any, other African-Americans on the field when Smith played, but he says he didn’t feel uncomfortable in lacrosse and wasn’t subjected to racially charged comments.

“At least not to my face,” Smith said. “I’ll put it to you like that. I don’t know what other people say [privately], but I didn’t get that feeling, at least not a lot.”

In the first article in this Black History Month series, UVA alumna Cathy Grimes-Miller reflected on her experience on Grounds.

“I think that because I was on the women’s basketball team,” Grimes-Miller said, “I was somewhat insulated from some of the larger issues that a Black student who was not part of a group coming in might have been exposed to, or I didn’t face a lot of the same challenges because I already had a built-in support system. A lot of my [older] teammates kind of took us under their wings and guided us and supported us and showed us the ropes.”

Smith had a similar experience with lacrosse. “I agree with her 110 percent,” he said. “It really is like you have a built-in buffer a little bit. You don’t have to join a frat, because the team is your frat or sorority. It’s definitely an advantage.”

Overall, he said, he loved his time on Grounds. “I can’t speak enough about the people that I’ve met and I’ve stayed in touch with,” said Smith, whose friends include Tom Henske and the former Anna Yates, who played men’s soccer and women’s lacrosse, respectively, at UVA. “There weren’t a whole lot of bad memories, if at all.”

After graduating from UVA, where he majored in sociology, Smith moved to New York. He eventually landed with ESPN, where he worked in advertising and marketing for 13 years. He later worked at the Tennis Channel for about two-and-a-half years.

Smith and his ex-wife have joint custody of their three daughters, who live with their mother near Norwalk in Wilton, Conn. He didn’t play professional lacrosse after graduating from UVA, but he’s become active in the sport again, this time as a coach.

At Ridgefield High School, which won a state championship in Connecticut last spring, Smith oversees the defense. Ridgefield’s head coach is former Syracuse All-American Roy Colsey. One of Colsey’s sons, Ryan, will join the team at UVA in 2022-23.

“I hopped on midway through last year, because Roy was just like, ‘I need help. I’m concentrating a lot on the offense, and I need a defensive perspective,’ ” Smith recalled.

He was between jobs at the time, Smith said, “so I was just like, ‘Well, I’m not doing anything, so I might as well.’ And now I to want to do this more full time.’

Smith also coaches in the Eclipse Lacrosse Club, which is based in New Canaan, Conn.

“Roy hooked me up, and I’ve had a great run with them,” Smith said. “Lacrosse is six degrees of separation. If you know someone [in the sport], you know pretty much everyone. It’s been a great run and I can’t wait to get it popping again.”

Lars Tiffany, who succeeded Starsia at UVA after the 2016 season, is also from the Syracuse area, and Smith has known him for years. They played summer league lacrosse together and still talk regularly.

“He was a big influence on me as far how to play the game,” Smith said. “Play with respect. What I tell my players is this: Play the game fast, physical and smart. Give me those three things and I can work with them.”

Smith said he’ll never forget a lesson Starsia imparted to his players at UVA. “He said, ‘Guys, the world has enough clowns. Be a leader.’ That’s all he said to say, and I share that with my players, too. Don’t be a clown. Be a leader.”

Two years after Smith wrapped up his college career, Virginia won the NCAA title for the first time since 1972. Starsia went on to win three more NCAA championships with the Hoos, in 2003, 2006 and 2011, and Tiffany has guided them to back-to-back national titles.

“To be 100-percent honest with you, part of me is a little bit jealous,” Smith said, “but that’s just me being the competitor that I am. At the same point in time, I know I’m one of the old-school guys that laid the foundation so those guys could succeed. And that makes me very proud.”

Since Smith’s graduation from UVA, other Black players have excelled in lacrosse there, including Jonny Christmas, the late Will Barrow and the Bratton brothers, Rhamel and Shamel, and he believes interest in the sport is increasing among African-Americans.

“I think it’s trending that way,” Smith said, “and as long as we keep moving up and not staying stagnant, that’s a good thing. I would like to see more African-Americans involved with coaching.

“First of all, I think it’s healthy for everybody to actually see diversity. I grew up playing box lacrosse with the Onondaga tribe. It’s the Six Nations, the Iroquois. That’s really where lacrosse started, and I stay in touch with those guys a lot.

“People say it’s a white sport. No, it’s not a white sport. It’s a Native American sport played predominantly by white kids. So I have to educate people a lot about that.”

To receive Jeff White’s articles by email, click here and subscribe.