'72 Team Remains One for the Ages

By Jeff White (jwhite@virginia.edu)

VirginiaSports.com

CHARLOTTESVILLE – Fifty years ago this June, the University of Virginia men’s lacrosse team made history. The Cavaliers, whose head coach was 27-year-old Glenn Thiel, won the program’s first NCAA championship, defeating Johns Hopkins 13-12 in the title game at Byrd Stadium in College Park, Md.

“We had a special group of guys who could really, really play,” recalled Tom Duquette, a junior attackman on the 1972 team. “The combined lacrosse IQ of that team was unbelievably high.”

UVA has collected six more crowns since then: four under Dom Starsia (1999, 2003, 2006 and 2011) and two under current head coach Lars Tiffany (2019 and 2021). But the first NCAA title remains special, for countless reasons, and the 1972 team will be recognized, along with the 2011 team, Saturday at Klöckner Stadium, where No. 7 UVA meets No. 15 North Carolina in a 4 p.m. game that ESPNU will televise.

“We’ll parade out on the field in various stages of canes, wheelchairs and walkers,” Doug Tarring said, laughing.

Tarring was a senior attackman on the 1972 team, whose assistant coaches included his brother, Bob. The NCAA men’s lacrosse tournament has become a nationally televised affair whose final weekend often takes place in NFL stadiums, but it was in its infancy then.

Until 1971, the NCAA did not hold a tournament in men’s lacrosse. The U.S. Intercollegiate Lacrosse Association chose the national champion—or champions—at the end of each season.

In 1952, for example, the USILA had awarded the national title to Virginia, a first for the program. In 1970, the USILA recognized UVA, Hopkins and Navy as tri-champions.

In 1971, Virginia entered the inaugural NCAA tournament as one of the favorites, but bowed out with a first-round loss to Navy. The Wahoos came into 1972, their third season under Thiel, looking for redemption, but nearly missed the NCAA tournament.

“I believe we had the most talented team in the country, but we didn’t play to that level until the tournament,” Tarring said. “If you look at our season in ’72, we were kind of underachievers.”

Why that was the case is “the $64,000 question for which I don’t have any explanation,” said Duquette, who lives in Virginia Beach. “The margins were not great in those losses. We never got blown out, and we were in close games … There was nothing crazy. That happens when you play sports, and thankfully we got the chance to atone for some of those missteps in the tournament.”

Virginia closed the regular season against Washington & Lee in Lexington. A loss would have extinguished the Hoos’ hopes of making the eight-team NCAA tournament, and they trailed 7-3 early in the second half. But UVA rallied for a 10-9 victory, “and suddenly we’re now coming into [the NCAA] tournament via the back door,” Rodney Rullman recalled, “and I mean back door.”

Rullman’s brother, Charlie, had helped the Cavaliers win a share of the national title in 1970, his senior season. Rodney Rullman was a freshman on the 1972 team, and he split time in goal with classmate Scott Howe for most of the regular season. Rullman got the start against W&L, however, and his spectacular performance helped him lock down the job.

“It was one of those types of games that just fell into place,” said Rullman, who like Tarring lives in Charlottesville. “It was just one of those days that goaltenders don’t plan on.”

Rullman wasn’t the only freshman in Virginia’s lineup. Overall, though, the Cavaliers were an experienced team.

UVA’s veterans “carried me and gave me a certain kind of confidence that if I could just settle my own butt down and do my job, they would take care of business defensively and offensively,” said Rullman, who grew up on Long Island, N.Y.

“I had a damn good defense in front of me. I also had a damn good offense down at the other end of the field, and it kind of dawned on me that if I could just get my act together, freshman or not, and do my job, this defense and this offense would probably take me to the promised land, so to speak.”

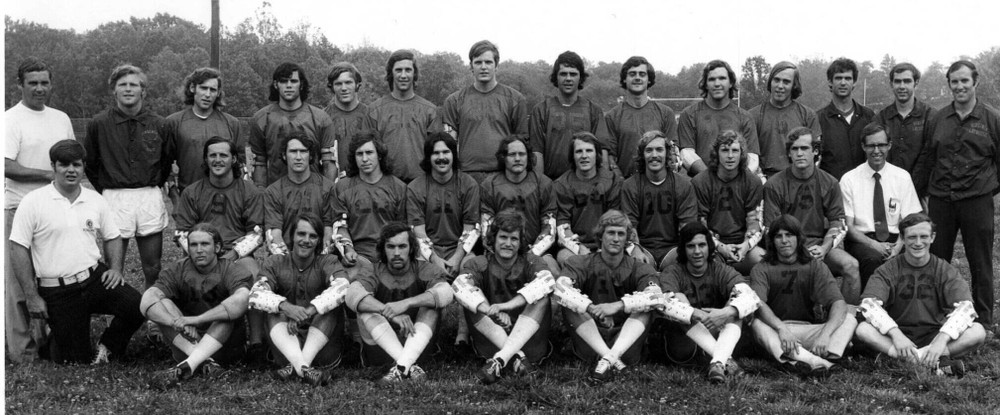

1972 team

Once the Cavaliers made the NCAA tournament field, Tarring said, they were determined not to squander the opportunity in front of them. “That really brought us together as a team,” he said, “and that’s why we played our best lacrosse for three weeks.”

Virginia’s opponent in the quarterfinals was Army, one of the tournament favorites. Army’s field was unavailable that day, however, and so the game was played at Scott Stadium.

“If the truth be told, our draw was sort of providential,” Duquette said.

In front of a crowd of 3,000, UVA dispatched Army 10-3 to advance to a semifinal matchup with Cortland State, which had upset Navy in the quarterfinals. The game was played on Cortland State’s campus, about 35 miles south of Syracuse, N.Y., and drew an overflow crowd.

That didn’t deter UVA. The Cavaliers had pounded Cortland State 17-5 early in the regular season, and they romped in the rematch, too, winning 14-7 to advance to the NCAA championship game. Their opponent in College Park would be Hopkins, which had upset top-seeded Maryland in the other semifinal.

“If you look at the way the draw fell, our draw ended up being the best,” Tarring said. “Whereas Hopkins had to play Maryland in the semis, we got to play Cortland State.”

Storylines abounded in the championship game. In 1970, Duquette’s freshman season, Virginia had crushed Hopkins 15-8. In 1971, the Cavaliers had defeated the Blue Jays again, but this time in double overtime.

There was no shot clock in lacrosse back then, and the ’71 game was close, Duquette said, largely because Hopkins head coach Bob Scott had his team hold the ball for long stretches. Scott had been inspired by Virginia’s tactics in its storied upset of No. 2 South Carolina in men’s basketball that January.

“That was the game in which Barry Parkhill put Virginia basketball on the map,” Duquette said. “Coach Scott had seen that and realized that his undermanned team might be able to use a similar strategy. And it was unbelievably effective.”

The Blue Jays had more firepower when they came to Charlottesville to face UVA during the 1972 regular season, “and we were psyched to be able to play a real lacrosse game on a nice spring day in Scott Stadium,” Duquette said. “And damn if they didn’t hold the ball again. It was one of the most devastating psychological ploys I have ever experienced.”

Hopkins won that game 13-8, which added another twist to the rematch.

“In the second half, I decided to see what Coach Scott would do if someone held the ball against them,” Duquette said. “So I just went out in the corner and held the ball and stood and watched the Hopkins bench go crazy. And finally they sent a second [defender] and I waited, waited, waited and ran around both of them and threw it to Petey Eldredge, and he scored. And I did that twice.”

The game had started poorly for the Cavaliers. Rullman gave up two goals in the first 79 seconds, after which he called a timeout.

“I cracked,” Rullman told reporters after the game. “I was in shock.”

When the game resumed, Rullman steadied himself, and the Hoos went into halftime with a 7-5 lead. Hopkins led 9-8 after three quarters, but Virginia scored the first four goals of the final period, the last of which, by Duquette, made it 12-9 with 6:22 remaining.

The Blue Jays didn’t fold. They answered with three straight goals to tie the game.

“The game was phenomenal,” Tarring said. “We’d go up, they’d go up.”

Rullman said: “It was truly a seesaw game. Back and forth and back and forth.”

The atmosphere at Byrd Stadium, Duquette said, was “electric, and it was really cool to be there.”

It was even cooler to win, and with 4:11 remaining, Eldredge scored an unassisted goal to put the Hoos ahead 13-12. Coming out of a timeout with seven seconds left, the Blue Jay had a chance to force overtime.

“They ran their play,” Rullman said, “and let’s give credit where credit is due, the play worked pretty well. They did get a guy open, maybe 10 yards up off the top of the crease, and he took a shot that went low. I saw it, but I did not save it. I think some people may think I saved it. No. If I remember correctly, I saw the shot and I knew where it was headed, but it hit Boo Smith’s foot, one of our defensemen. It wasn’t me.”

Time ran out, and UVA celebrated its historic feat. Eldredge, a senior midfielder, led the Hoos (11-4) with four goals against Hopkins, and freshman middie Richie Werner and sophomore attackman Chip Barker added three apiece. Senior attackman Jay Connor contributed one goal and three assists, and Duquette finished with two goals and three assists. Rullman made 11 saves.

Rodney Rullman (center) in goal

Six Cavaliers received All-America recognition in 1972. Eldredge and Connor were first-team selections, defenseman Bruce Mangels and middie Doug Cooper were second-team picks, and Duquette and middie Bob Proutt earned honorable mention.

“Eldredge was maybe as a good a player as there’s ever been in the program,” said Tarring, the longtime analyst on radio broadcasts of UVA games.

Sports Illustrated covered the championship game and wrote an article, titled Bubble Bath For The Blue Blue Jays, that detailed the Cavaliers’ mode of transportation from Charlottesville to College Park.

“We didn’t take a bus. We drove as individuals,” said Duquette, who arrived in his Ford Pinto.

SI wrote that Thiel’s team “drove into town in all manner of dinged-up Pintos, aging Chevy IIs, faded Falcons and a 10-year-old Dart with a bad list to the right and more rust than paint. One group rolled up in a boss white Buick convertible, class of the mid-‘60s, with no hubcaps.”

It was a different era. The Blue Jays, expecting to prevail, had stocked their locker room with champagne for a postgame celebration. They drank it anyway.

“What the hell, we’re not going to throw it away,” Scott said after the game. “The guys are thirsty. Besides, we don’t have anything to be ashamed of.”

The Cavaliers’ rewards for winning the NCAA championship included more than a trophy.

“The players wanted some beer last week after they beat Cortland,” UVA athletic director Gene Corrigan told reporters afterward. “I said no, but promised them a keg if they won the title. I’ve got it, too.”

In the ‘70s, the Hoos played most of their home games on a field near where the George Welsh Indoor Practice Facility now stands, and “we provided a pretty good show,” Duquette, who went on to win seven state championships as head coach of the Norfolk Academy boys team.

“The game, with a capital G, sells itself, just because of all the things that it is. It’s physical, it’s high-scoring, it’s fast, all that stuff. Put that together on a nice spring afternoon in Charlottesville, and it’s a pretty good way to spend an afternoon if you’re a spectator. It’s a pretty good way to spend an afternoon as a player as well.”

Tarring, who won seven state titles as head coach at St. Anne’s-Belfield School in Charlottesville, remembers that UVA home games “would be packed with students. The town had no clue what lacrosse was back then—we couldn’t find a ball boy in ’72—but the students really got excited. There was no price [for admission], and you could bring beer and sit five feet from the sideline with your cooler. We’d draw 7,000 or 8,000 people for a lacrosse game on a nice Saturday.”

The 1972 team has lost several members over the years, including players Eldredge, Rick Bergland and Bill Kearney; media relations representative Doyle Smith, who remains a legend in the sport; and Corrigan, who coached lacrosse before becoming AD.

“That’s the reality of 50 years,” Tarring said. “But amazingly it’s still a pretty good group of guys that have stayed together.”

Several of the former Cavaliers, including Rullman, still play lax together. Thiel won’t be able to make it to Charlottesville this weekend, Tarring said, but a strong turnout of players from that championship group will be back for the reunion.

At the close of the 1960s, Tarring said, Hopkins, Maryland, Navy and Army were widely considered the best programs in college lacrosse. The advent of the NCAA tournament helped change that.

In 1971, Cornell became the sport’s first NCAA champion, and UVA reached the peak a year later. With the title, Tarring said, UVA “gained credibility as being one of the premier programs in the country. There’s so much history in that ’72 team. That senior class and those classes kind of changed the perception of Virginia lacrosse.”

To receive Jeff White’s articles by email, click the appropriate box in this link to subscribe.