Ham Helped Blaze Trail for Cavalier Football

By Jeff White (jwhite@virginia.edu)

VirginiaSports.com

CHARLOTTESVILLE –– Among those who will be recognized during the Virginia-Duke football game Saturday at Scott Stadium are Harrison Davis, Stanley Land, Kent Merritt and John Rainey. When they enrolled as first-year students in 1970, they became the first African-Americans to receive football scholarships from the University, and their historic impact on the program has been well-chronicled.

Not so widely known is the story of Gary Ham, who’ll be honored with them Saturday.

Ham enrolled at UVA on an Army ROTC scholarship in 1969, with no intention of playing football. On his floor in Echols dormitory were a couple of football players, though, and Ham watched games from the stands at Scott Stadium that fall.

The Cavaliers dropped their final six games and finished 3-7. Ham thought he might be able to play at the college level, and so he tried out for the team early in the spring semester of his first year. The coaches liked what they saw and invited Ham, a 5-foot-10 cornerback, to join the program as a walk-on.

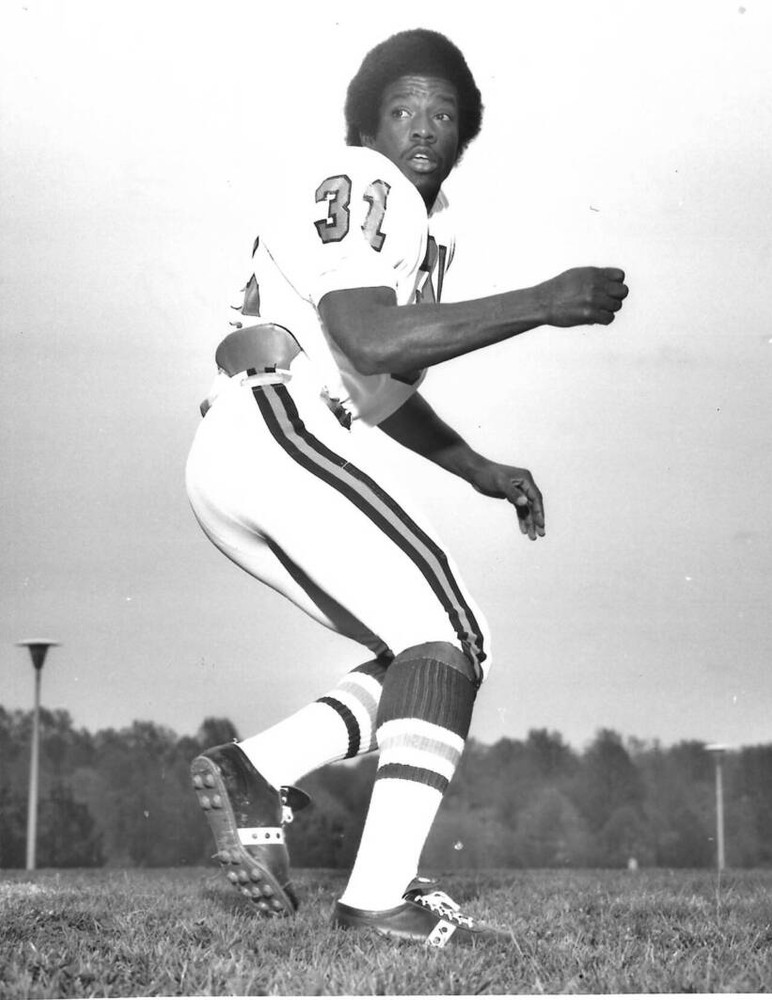

In 1970, when Davis, Land, Merritt and Rainey played for Virginia’s freshman team, whose coach was Al Groh, Ham was the only African-American on the varsity. The Wahoos had a new head coach, Don Lawrence, and he “was the one that pretty much kind of recruited me and encouraged me to stay with it,” Ham, who wore jersey No. 31, recalled in a recent Zoom interview.

To be saluted as one of the program’s pioneers will be an immense honor, said Ham, who lives in the Rochester, N.Y., area with his wife, the former Harriet Pierce. They’ve been active in Christian ministries for more than four decades.

“I just feel humbled by the whole thing,” said Ham, a pastor who turns 70 next month. “There’s four major things that I’m so thankful for about my experience at UVA, and now for this to happen, it’s overwhelming.”

First, Ham said, “I got a chance to play Division I football. How many kids get a chance to play Division I football?”

Second, UVA “prepared me for my life work,” Ham said. “You get four years of college education and it gives you something, it prepares you for life, for work. It helps you learn how to do things that you need to do if you’re going to achieve something in life. And so I went through ROTC and that prepared me to serve our country, which I was very proud of.”

UVA also “was the place where I met my wife, and we’ve been married now for 47 years,” Ham said. “She graduated the same year that Kent and [the other three African-American players] graduated. She was in that class. But the most important thing that happened at UVA was that in my senior year I re-dedicated my life to Jesus Christ.”

Ham said he heard a preacher on Grounds during Black History Month in early 1973, “and I realized then and there that I was falling short of God’s plan for my life, and that was a major turnaround of my life. I recommitted my life to Jesus Christ.”

For his final two years at UVA, said Ham, a sociology major, he was on football scholarship. A reserve as a junior in 1971, he headed into his senior season hoping to carve out a significant role on the team. It didn’t happen.

“My junior year was wonderful,” Ham said. “You could really begin to see some potential, and actually I had traveled with the team [to road games] in my junior year. But I came to camp in 1972 injured.”

He’d sprained his knee playing sandlot football in Hampton. “It was one of the worst decisions of my life,” Ham said, shaking his hand. “The coaches were upset with me, and I was upset with myself.

“I wasn’t a Kent Merritt or a John Rainey. Those guys were amazing athletes. I was just a hard-working guy that had some skills. So when I came to camp my senior year with that kind of injury, then my chances of doing anything were really minimized.”

Gary Ham

Ham was born in Roanoke, his parents’ hometown, but spent little time there. “When I was 2 years old, my dad joined the Air Force, and then we started traveling,” he said. “I spent three years in Japan. I spent six years in Minot, North Dakota, three years in Germany. So it was all over the place.”

When Ham was in high school, his father was stationed at Ramstein Air Force Base in Kaiserslautern, Germany, and the family lived in a military community called Vogelweh. Ham played American football in high school. “It was not as competitive as it would have been in the United States, of course, but we were pretty competitive,” he said.

When his father’s duty station in Germany ended, he was assigned to Langley Air Force Base in Hampton. Ham wanted to attend college and began researching schools in the Commonwealth of Virginia. After applying to UVA, he was accepted and decided to head to Charlottesville.

Not until 1970 did the University enroll its first class of undergraduate women. So Ham arrived at a school that was not co-ed and whose undergraduate student body included “21 or 22” African-Americans, he said.

He had experience in similar settings.

“All my life traveling with my dad in the Air Force, there were many situations where I was the only person of color,” Ham said. “So all my life I was accustomed to being a minority. It toughens you up. It really does. It never stops hurting, if you hear somebody say something or somebody does something because of the color of your skin. The pain will always be there, but there’s more resilience after time, and I have to say that when I got to UVA I never heard anybody call me a name. No one really treated me ill on the team.”

He credited such teammates as Gary Helman, a standout running back who was one of the Cavaliers’ captains.

“I remember we were doing a goal-line scrimmage [in practice],” Ham said. “I was on the defense, and we were going against the offense, and the hole opened up, and I intuitively knew that somebody was coming through that hole. We were playing goal-line defense, and I got as low as I could, and then there was this major impact.

“I think I was knocked out for a few seconds. The next thing I knew, the guys were patting me on the back because I was able to stop Gary Helman before he crossed [the goal line], and the guy who was really applauding me most was Gary Helman. He said, ‘Well done, Ham, well done.’ So when you have a guy like Gary Hellman affirm you in that way, who’s gonna mess with you? Who’s gonna talk about you? I had a couple of other moments like that, and that’s how I got the scholarship, because I just stuck my nose in places and it worked out for me on the field.”

The African-American students who entered UVA in 1969 developed a strong camaraderie, Ham said, and he spent much of his time with that group. He didn’t interact a lot with Davis, Land, Merritt and Rainey.

“Obviously, I had a lot of respect for those men, and like everybody else I was so glad they came and became part of the team,” Ham said. “I really thought they were going to take us to another level, believed in it, and of course they did help change the team a whole lot. But I was with a group of people, and we connected with an African American church there in Charlottesville, and we developed some relationships and friendships there too.”

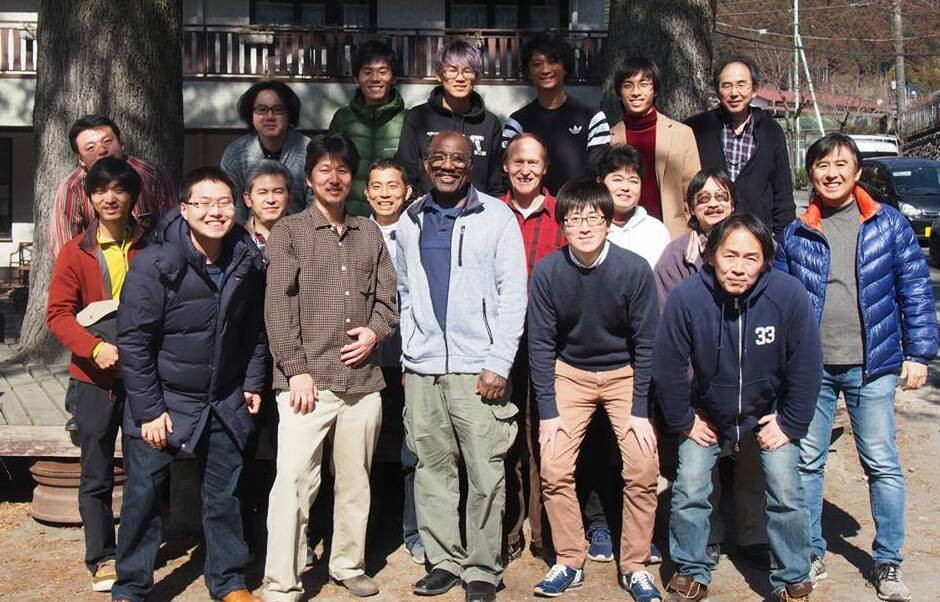

Gary Ham (center) in Japan

His senior football season didn’t turn out as Ham hoped, but he competed as a jumper on Virginia’s track & field team, coached by Lou Onesty, in the spring of ’73. “I didn’t letter in football, but I lettered in track,” Ham said.

After graduating from UVA, he spent four years in the U.S. Army. Then he attended Elim Bible Institute in Lima, N.Y., and entered the ministry after graduating in 1980. The Hams spent two years in Franklin, a small city about 45 miles west of Norfolk, and then relocated to the Tidewater area.

Apart from the two years (1986-88) they spent in Nigeria as missionaries, the Hams were mostly based in Hampton Roads until 2002, when they moved to the Rochester area. Ham served as the Elim Fellowship’s director of international ministries from 2002-08.

“All the work I have done has been for the Lord,” Ham said. “Every bit of it. It is responding to the call of God upon my life and my wife’s life. It’s taken us to almost 35 different countries, where we’ve served in unbelievable situations and circumstances, and we’re still working.”

Ham and his wife, who grew up in Newport News, have “three sons, three beautiful daughter-in-laws, and nine grandchildren,” he said, smiling.

He hasn’t been back to Charlottesville for several years, but he catches Virginia football games on TV “all the time,” Ham said.

He rejoined the program in a new capacity for a game on Nov. 28, 1998. Ham, who was living in Hampton at the time, was in Blacksburg that day to witness perhaps the most memorable comeback in UVA history. He’d been invited to lead the chapel service for the players the night before the game.

For the Hoos, the service went better than the first half of the game. Virginia trailed 29-7 at the break, and Ham was among those lamenting the situation at Lane Stadium.

“I said, ‘God, they’ll never have me back again,’ ” he recalled, laughing. “I said, ‘God, do something.’ ”

His prayers, and those of UVA fans everywhere, were answered. The Cavaliers rallied to win 36-32.

“It was an amazing game,” Ham said.

To receive Jeff White’s articles by email, click here and subscribe.